Denver’s latest stab at guiding development and land use for the next decade or two in the growth-fatigued city has added even more complexity to an evolving plan.

City officials are proposing four classifications to promote varying degrees of change or stability, neighborhood by neighborhood, as part of the updated “Blueprint Denver” plan. Their aim is for a new level of sophistication that might stave off some of the intense development and rezoning fights seen in recent years.

Planners are taking that and other proposed changes on the road in coming weeks to community workshop meetings across the city. The first is Tuesday night at 5:30 p.m. at Thomas Jefferson High School in southeast Denver.

The 2002 Blueprint Denver land use and transportation plan is one of four plans undergoing updates or being written for the first time as part of a two-year citywide planning effort called “Denveright.”

Related Articles

- November 29, 2017

Denver releases a wishlist of sidewalk and trail projects. It would cost at least $1.2 billion

- September 14, 2017

Is your area a “community center” or “regional corridor”? Blueprint Denver update will influence growth patterns

- March 18, 2017

Denver’s population is surging. Its summers are getting hotter. How will the city’s parks system adapt?

- December 12, 2016

Denver is absorbing a lot more people, but it’s not more densely populated than 1950

The original Blueprint plan’s simplicity — pegging every inch of the city as an area of change or stability — was hailed as innovative 16 years ago, but during the recent population boom its classifications have fed into disputes during heated rezoning fights.

In an overview of the latest changes since the last round of meetings in September, principal city planner David Gaspers and Denver planning chief Brad Buchanan said the four proposed categories for types of change would allow for the highlighting of prevailing needs in different parts of the city.

“It weights different kinds of change over another,” Buchanan said.

Only in some areas, such as the parking lots around the Pepsi Center and Elitch Gardens, is there such a demand for redevelopment that a transformation of their character is warranted in coming decades, Gaspers said.

On the other end of the spectrum are the quiet, stable single-family neighborhoods that have been most resistant to denser development. Those might land in a category currently dubbed “enrich” — a delicate way of saying that residents might be open to light redevelopment that provides more diversity of income, education and housing stock, such as backyard cottages or townhomes on busy corners. But they don’t want huge changes.

In between are “connect” neighborhoods that are similarly stable but in need of closer proximity to amenities such as grocery stores, education, jobs or shopping. And another category, called “integrate,” might apply to areas where longtime residents are at risk of being squeezed out, with a need for city policies and development that improves housing affordability.

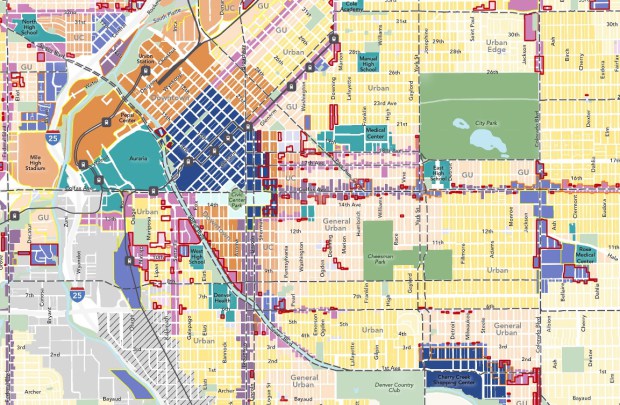

A map showing where the categories would be applied wasn’t yet available. But the concept joins other still-evolving proposals for a more concrete mapping of the entire city that labels places with neighborhood contexts, ranging from suburban to different levels of urban to downtown. That map also differentiates between travel corridors and community nodes and centers of different types, and it classifies residential areas by the density of buildings desired, from low to high.

Denver’s Department of Community Planning and Development is aiming to produce a draft Blueprint plan in coming months, with adoption of a final plan by the City Council this summer.

In formulating a new Blueprint roadmap, city planners are navigating conflicting pressures. Urban advocates have stood up at Blueprint meetings to argue for a plan that prepares a wider swath of the city to absorb the future population growth projected by demographers, resulting in wider-scale densification.

But some fiercely protective neighborhood advocates want assurances that their smaller-scale areas will survive intact.

“Blueprint Denver is so hard to understand for the public,” said Councilman Wayne New, who represents central Denver, during a recent council committee briefing. He urged Gaspers to make it easy for attendees of the upcoming meetings to understand how the new Blueprint plan will affect their neighborhoods — and to dispel any misconceptions about changes that might be in store.

“I don’t want people to be scared about what’s going to happen,” New said.

Blueprint Denver meetings

Most meetings are set to run two hours:

- 5:30 p.m. Tuesday at Thomas Jefferson High School, 3950 S. Holly St.

- 5:30 p.m. Wednesday at Laradon, 5100 Lincoln St.

- 6:30 p.m. Thursday at Potenza Lodge Hall, 1900 W. 38th Ave.

- 6 p.m. Thursday at District 3 Police Station, 1625 S. University Blvd.

- 5:30 p.m. Feb. 27 at the Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales Branch Library, 1498 Irving St.

- 6 p.m. March 1 at All Saints Parish Hall, 2559 S. Federal Blvd.

- 5:30 p.m. Mar. 6 at Community of Christ Church, 480 N. Marion St.

- 6 p.m. March 7 at Evie Garrett Dennis Campus, 4800 Telluride St.

- 6 p.m. March 8 at Valverde Elementary, 2030 W. Alameda Ave. (Primarily in Spanish.)

- 6 p.m. March 14 at DSST Byers School, 150 S. Pearl St. (No Spanish interpretation available.)

- 5:30 p.m. March 15 at DSST Stapleton High School, 2000 Valentia St.