Statistics Canada reports growth data on Thursday that will confirm the nation’s economy has entered rarefied territory.

Economists are forecasting an expansion in second-quarter gross domestic product at about the same 3.7 percent pace recorded in the first three months of this year. Even with an anticipated second-half slowdown, that should leave Canada flirting with 3 percent growth for all of 2017.

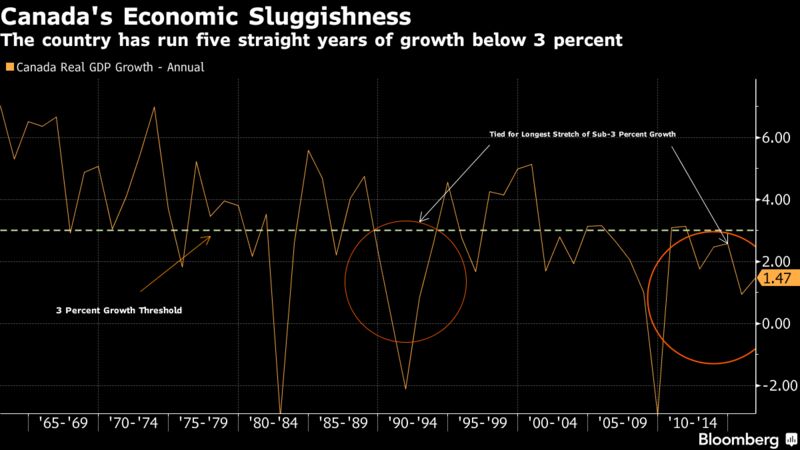

If that happens, it would end a five-year stretch of sub-3 percent growth that’s already tied as the longest on record in data going back to 1926. The nation is benefiting from a confluence of developments that include a synchronized global recovery and rising trade volumes, the bottoming of the oil shock in western Canada, federal deficit spending, rising industrial production in developed economies and soaring home prices in Toronto and Vancouver.

The surprise surge in activity over the past year is having one lasting impact: it will eliminate fully Canada’s existing economic slack in coming months, if it hasn’t already. That would be quite a milestone. According to Bank of Canada estimates, the economy has been in a state of excess capacity for 35 straight quarters.

The mix of no slack with low potential growth means interest-rate increases are almost certainly in the cards even at very low growth rates since it won’t take much to push the economy into excess demand, according to Jean-Francois Perrault, chief economist at Bank of Nova Scotia.

The Bank of Canada estimates the nation’s economy can’t grow much beyond 1.4 percent before fueling inflation. In other words, Canada may be entering an era of slow growth and rising interest rates, which is not exactly a dream scenario for policy makers.

“There is no way around it,” said Perrault, “Two percent is not high compared to history, but it is compared to trend.”

Fiscal Impact

In addition, fiscal stimulus may no longer be needed in an economy with no slack and low potential growth as it can accelerate rate increases and crowd out private players.

That doesn’t mean arguments can’t be made for bigger government. There could be an argument for financing productivity-enhancing infrastructure or redistributing income more fairly. More government debt and less private debt is also probably more stable in a world with record household debt and relatively low government borrowings.

But the tradeoffs to deficits are becoming more stark.

“The fact that you are running expansionary fiscal policy at a time when growth is as strong as it is, clearly you will have higher interest rates than you would otherwise have,” Perrault said.

In some ways, the latest growth spurt merely serves to highlight how sluggish Canada’s economy has become in recent years.

Indefatigable Shoppers

No one predicted the bump up in growth, in large part because no one expected Canada’s highly indebted consumers would have the capacity to continue to press on the accelerator. But they did.

Growth in consumption — which accounts for about 57 percent of real GDP — is forecast to surpass 3 percent in 2017, the first time that’s happened since 2010. In a January survey of economists, the highest estimate for consumption growth was 2.2 percent, with a median forecast of 1.9 percent.

There are two main reasons for the better-than-expected numbers.

One, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s fiscal policy has clearly had an impact, particularly tax cuts and enhanced child benefits that came into effect last year. More significant may be a surge in home prices and housing wealth in Toronto and Vancouver that’s prompting households to ramp up spending. The value of residential real estate in Canada jumped by C$384 billion ($308 billion) in the year through March, Statistics Canada reported earlier this year.

Neither factor is seen as a sustainable source of growth, and a payback effect is expected in coming years. Economists estimate household spending growth will fall back below 2 percent by 2018, which is a slower pace than the overall economy — a rare occurrence. Consumption has only lagged the economy once in the past 15 years.

Mean Reversion

That will likely mean the Canadian economy’s moment in the sun will be brief. Economists are already forecasting a sharp decline is already under way this quarter and the central bank expects growth will fall back quickly to about 2 percent levels next year, bringing it closer in line with longer-term fundamentals that are hobbled by an aging labor force and falling productivity.

Mark Chandler, head of fixed income research at Royal Bank of Canada, said that residential investment and the wealth impact of housing have been accounting for about half a percentage point of growth.

“A good chunk of it has been tied to house prices,” Chandler said. “Our best guess that starts to roll off in the second half of this year.”